RESEARCH ARTICLE

Tissue-specific Effect of Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation on the Oxidative Post-translational Modifications in the Rat

Nilanjana Das1, Chandan Kumar Jana2, *

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2016Volume: 3

First Page: 196

Last Page: 202

Publisher Id: PHARMSCI-3-196

DOI: 10.2174/1874844901603010196

Article History:

Received Date: 28/12/2015Revision Received Date: 13/07/2016

Acceptance Date: 15/07/2016

Electronic publication date: 19/08/2016

Collection year: 2016

open-access license: This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 International Public License (CC BY-NC 4.0) (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/legalcode), which permits unrestricted, non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background:

Coenzyme Q (CoQ), a component of almost all cellular membranes, has been postulated to act as an antioxidant due to its capacity to recycle the oxidized alpha-tocopherol and scavenge peroxy radicals.

Objective:

The present study was performed to investigate the in vivo effects of a long-term supplementation of CoQ10 on oxidative protein modifications in some tissues as the plasma and the brain of the Sprague Dawley rat.

Method:

Male Sprague Dawley rats of 14 months age were supplemented with 150 mg/kg/d of CoQ10 and the effects on oxidative post-translational modifications analyzed after 13 weeks of supplementation.

Results:

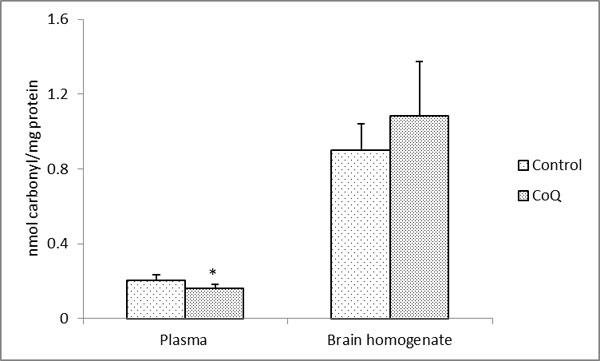

Supplementation of CoQ10 for thirteen weeks in adult animals resulted in decreased protein carbonyls due to oxidative post-translational modifications in the plasma (approximately 21%) but an increase of the same in the brain tissue homogenate (approximately 21%) was observed. These alterations were statistically significant in the former while the increase in the latter was statistically not significant.

Conclusion:

The results suggest a tissue-specific effect of dietary supplementation of CoQ10 on oxidative post-translational modifications by carbonylation in the rats.

INTRODUCTION

Coenzyme Q (CoQ), a quinone derivative, is known to transfer electrons from complex I and II to complex III of the electron transport chain of oxidative phosphorylation [1-5]. It is believed that this molecule can act as an antioxidant although an opposing effect has also been postulated. Its pro-oxidant role may be related to the auto-oxidation of the mitochondrial CoQ (ubisemiquinone) to generate the O22- radical which is a progenitor of other oxygen free radicals [6, 7]. Its capacity to act as an antioxidant is due to its capacity to interact with the tocopheroxyl radical regenerating the α-tocopherol [2, 8-13] which can in turn scavenge lipid peroxyl radicals [1, 8, 14-16] as also its direct interaction with peroxy radicals reducing them [2, 13, 15, 17-20]. This has directed studies towards investigating the role of CoQ as an antioxidant under in vivo conditions. Major studies on the role of this molecule includes 1) monitoring the level of the molecule in the different tissues following supplementation with different diet regimes in different animal models [21-26]; 2) the attenuation of the oxidative post-translational modifications [21, 27]; 3) reversal of the age-related deterioration of cognitive ability or learning ability [27, 28]; 4) alterations in level of mitochondrial α-tocopherol by the molecule [12]; 5) modulation of lipid peroxidation in diabetic models [29]; 6) reduction in H2O2-mediated DNA damage in human lymphocytes [30]; 7) alterations in gene expression [31, 32]; 8) correlation with male infertility [33] and its role in sperm motility [34]; 9) life span [24, 35-37], etc.

The effect of CoQ10 supplementation in the rat model has been described in a previous study wherein level of CoQ in some tissues such as the plasma, heart, skeletal muscles, liver, kidneys, whole brains following supplementation was determined along with the level of oxidative post-translational modifications of the whole homogenates and mitochondria of the liver and skeletal muscles, studying the rate of H2O2 production, the level of aminothiols in the plasma and antioxidative enzymes in some tissues of the Sprague Dawley rats [21]. However, subsequent to this report, species and tissue-specific biochemical responses have been reported from many laboratories. The present study was an attempt to understand the effect of a long-term supplementation with CoQ on oxidative post-translational modifications in some tissues of the rat as the plasma and the brain where the augmentation of CoQ10 in these tissues following supplementation has already been reported [21]. One of the important hypotheses of aging is the oxidative stress theory of aging which states that increased production of free radicals and the consequent targeting of biological macromolecules lead to accumulation of chemically as well structurally altered important macromolecules causing their age-associated dysfunction [38]. This has directed numerous studies towards development or screening of potential antioxidants which can efficiently quench the free radicals produced and can thereby attenuate the age-associated deterioration in physiological activities of the organisms. Modulation of such oxidative post-translational modifications is important especially in the long-lived post-mitotic tissues as the brain which is involved in the etiology of many age-related diseases as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, etc.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Q-Gel liquid (provided by Tishcon Corp., Westbury, NY, USA) contained coenzyme Q10 (36.7 mg/g), Span 80 (56.0 mg/g), glycerine (39.1 mg/g), Tween 80 (733.1 mg/g), d-α-tocopherol (7.1 mg/g), and medium chain triglycerides (128.0 mg/g). The supplemented diet was NIH-31 modified to contain 9.7% Q-Gel liquid with 3.24 mg CoQ10 and 0.7 IU α-tocopherol/g diet.

Animals and Coenzyme Q Supplementation

Studies were approved by and conducted at the University of Southern California in adherence to the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, promulgated by the National Institutes of Health. Animals were male Sprague Dawley rats of 14 months age at the time of initiation of supplementation. The animals were randomly assigned to normal groups and fed NIH-31 food or to the experimental group where they were fed NIH-31 supplemented with CoQ10. The supplementation protocol was essentially that followed in an earlier publication [21] with the rats receiving 150 mg/kg/d of CoQ10. The animals were euthanized after 13 weeks of supplementation.

Preparation of Tissue Homogenates

Plasma: Blood from male Sprague-Dawley rats was collected directly from the heart of CO2 euthanized animals using EDTA moistened needle and syringe containing approximately 50 ml of 100 mM EDTA solution for each ml of blood. The mixture was centrifuged at 2600 g for 5 min to separate the plasma.

Brain: Whole brain tissues were homogenized in 10 volumes (w/v) of 5 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), containing the protease inhibitors, leupeptin (0.5 mg/ml), aprotenin (0.5 mg/ml), pepstatin (0.7mg/ml) and 0.1% Triton X. The homogenate was centrifuged for 5 min at 700 x g at 4°C to sediment unbroken cells and cellular debris and the supernatant used for all analysis.

Measurement of Carbonyl Content in the Tissue Homogenates

Total protein carbonyl content was determined by a modification of the tritiated sodium borohydride reduction method of Lenz et al. [39], as described in detail in Kwong et al. [21]. The radioactivity was quantitated in a Tri-Carb liquid scintillation counter (Parkard BioScience, Meriden, CT, USA).

In case of the plasma tissues, the number of animals were four and three for the control and experimental groups, respectively, each animal being treated independently with triplicate measurements. In the brain tissue, the number of animals were six and three for the control and experimental groups, respectively, each animal being sampled separately with triplicate measurements.

Measurement of Protein Content

Protein content was determined using the BCA protein assay according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed for statistical significance using one-way analysis of variance and post hoc tukey t tests. Differences in the means with probability values (P) of 0.05 or less were considered to be significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The principal aim of this study was to investigate the effect of long-term supplementation of CoQ10 on the level of oxidative stress by measuring post-translational protein modifications in some of the tissues of the rat as the plasma and the brain. Although not known to increase life span of any laboratory mammalian model including that of rodents [24, 32, 35], there has been widespread usage of the molecule as an over-the-counter supplement due to its perceived role as an antioxidant. Though there has been no increasing evidence on possible pro-oxidant role of the molecule [6, 7], some concerns have been raised that necessitate more research in this area to address these issues.

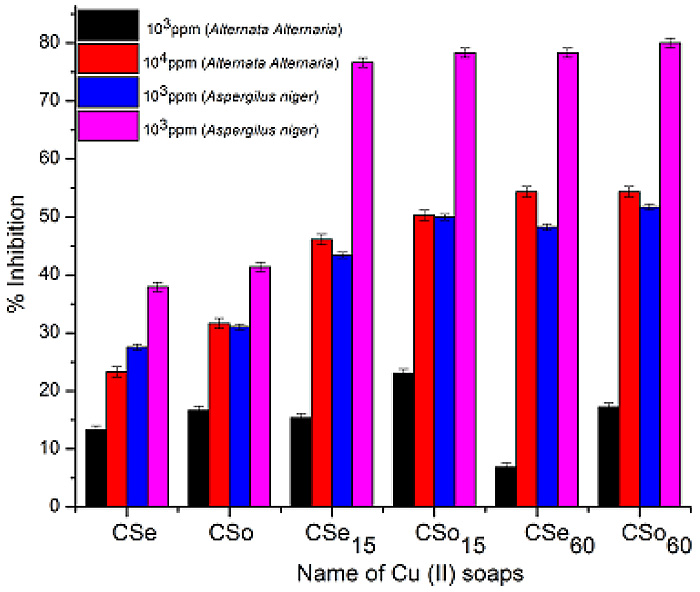

The long-term supplementation with CoQ10 in male Sprague Dawley rats showed an approximately 21% decreased in the level of carbonylation in comparison to control in the plasma proteins which was statistically significant (P < 0.003) (Fig. 1). On the contrary, there was 21% increase in the level of carbonylation in the brain whole homogenates (Fig. 1). However, this increase was not statistically significant (P < 0.083; significant at 92%). There could be several possible explanations for these observations. It is possible that the tissue-specific response may be caused by tissue-specific incorporation of the CoQ10 following supplementation. It has been reported that while the level of CoQ10 increased in the plasma (and other tissues) following supplementation [21, 22, 24], reports on its level in the whole brain homogenate have been controversial. In case of the rat with a similar supplementation regime as applied in this study, there was statistically significant augmentation of CoQ10 in both the homogenate as well as in the mitochondria of the brain tissue [21]. Similar report on increased level of CoQ10 in the rat cerebral cortex mitochondria following supplementation with it has been observed by Matthews et al. [25]. However, this is contrary to the report from mice [22, 24] where unlike other tissues, no significant increase in either the brain homogenate or mitochondria following augmentation with a range of dosage of CoQ10 were observed. Such differences in the reports in Kwong et al. [21] versus Kamzalov et al. [22] and Sohal et al. [24] from the brain tissue may be due to various factors as difference in the amount and regime of CoQ10 administration, tissue processing, animal husbandry, strain and/or species-specific differences. However, with a very high load of CoQ10 supplementation (654 mg/kg/d), the level of incorporated CoQ10 in the brain mitochondria increased significantly in the mice [22]. Nonetheless, by and large, the level of CoQ10 in the plasma was much higher as compared to the brain tissue, especially as compared to the homogenate values from all the reports [21, 22, 24]. Therefore, the possibility that the level of incorporation of CoQ10 in the brain was insufficient to mitigate the effects of the reactive species produced with age and/or oxidative stress in this tissue cannot be ruled out. Unfortunately, the high standard deviation of our biochemical assays could also have played a role in not providing an unambiguous finding in case of the brain tissue. Another explanation could be that since there are no age-related loss in CoQ10 level in the rat [40] and mice [24] brain, an increase in both CoQ9 and CoQ10 following supplementation with CoQ10 [41] could also have caused the molecule to act as a pro-oxidant in this tissue with a possible increment following supplementation of CoQ10 beyond the threshold level. This has also been reported previously where intake at a high dosage increased the age-associated cognitive decline [23]. However, no age-related alteration of CoQ10 in the rat plasma was observed [21, 42]. These tissue-specific differences may possibly be due to a reductive shift in plasma aminothiol status [21] with no compensatory alteration in the liver and skeletal muscle antioxidative enzymatic defense system following CoQ10 supplementation. Also, the inherent differences in the in situ level of oxidant generation and level of antioxidants could have a causal role for such differential findings. In case of a human study, a diverse genetic distribution and varied diet regimes need to be also taken into account.

|

Fig. (1). Protein carbonyl content in the plasma and brain homogenates in CoQ supplemented and control rats. All values represent the mean ± SEM. |

Coenzyme Q or ubiquinone (2,3-dimethoxy-5-methyl-6- multiprenyl-1,4-benzoquinone) - a component of almost all cellular membranes [43, 44] - exists in three oxidation states in the cell: ubiquinone (Q) which is the fully oxidized form; ubisemiquinone (QH) which is the partially reduced form and also a free radical; and ubiquinol (QH2) which is the fully reduced form [2, 43, 45]. Its antioxidant functions are related to its ability to stop lipid peroxidation reactions in the inner mitochondrial membrane [8, 15, 16, 45] and regenerating the oxidized antioxidant, α-tocopherol whereas its proxidant role is related to the auto-oxidation of ubisemiquinone resulting in superoxide anion radical generation in the mitochondria [6, 7]. Supplementation studies with CoQ have shown both a tissue- as well as a species-specific response. Earlier studies in the rats showed decreased carbonylation in the skeletal muscle mitochondria [21] while the level did not alter significantly in the skeletal muscle homogenate, the liver homogenate or mitochondrial fraction. This may be due to the preferential sequestration of the CoQ10 molecule in the rat skeletal muscle mitochondria in comparison to other tissues [21]. The carbonylation has also been reported to decrease in the brain tissue of mice with both a low (93 mg /kg/d) and high (371 mg/kg/d) level of supplementation [24]. Again species-specific differences might have played a role in these discrepancies as also differences in the dosage administered as contrary findings were reported in mice from the same laboratory using a different supplementation regimen. Protein oxidative damage was decreased in the mitochondria from the heart, liver, and skeletal muscle of the high-CoQ10-supplemented mice (~457 mg/kg/d) and, to some extent, in the brain mitochondria [27] when CoQ10 was administered in relatively high doses at a relatively late age when senescence-related alteration had already occurred. CoQ10 was also able to attenuate spatial learning with such a supplementation regime.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, from this and other previous studies, supplementation of CoQ10 to retard the aging process or age-related diseases cannot be recommended. Further research on its effects on specific disease conditions involving oxidative stress and/or mitochondrial dysfunctions need to be made since its effect on decreasing some of the oxidative stress parameters in the plasma and skeletal muscles (both homogenate and mitochondria) and liver (mitochondria) have been observed [21 and this report]. Since the level of protein carbonyls increase in the brain tissue, the potential of the reagent in controlling oxidative stress-related neurodegenerative disorders remain in question.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Prof. Rajindar S. Sohal, Timothy M. Chan Professor, Department of Pharmacology and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089-9121, U.S.A. for laboratory facilities and funds during the course of this work and Dr Surjya K Saikia, Department of Zoology, Visva-Bharati University for assistance with statistical analysis. The authors, N. Das and C.K. Jana, acknowledge Visva-Bharati University and Panchmura Mahavidyalaya, respectively, for necessary facilities.