RESEARCH ARTICLE

Antimicrobial Studies and Characterization of Copper Surfactants Derived from Various Oils Treated at High Temperatures by P.D.A. Technique

Renu Bhutra1, Rashmi Sharma2, Arun Kumar Sharma3, *

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2018Volume: 5

First Page: 36

Last Page: 44

Publisher Id: PHARMSCI-5-36

DOI: 10.2174/1874844901805010036

Article History:

Received Date: 26/7/2018Revision Received Date: 14/10/2018

Acceptance Date: 15/10/2018

Electronic publication date: 14/11/2018

Collection year: 2018

open-access license: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (CC-BY 4.0), a copy of which is available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode. This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Introduction:

Biologically potent compounds are one of the most important classes of materials for the upcoming generations. Increasing number of microbial infectious diseases and resistant pathogens create a demand and urgency to develop novel, potent, safe and improved variety of antimicrobial agents. This initiates a task for current chemistry to synthesize compounds that show promising activity as therapeutic agents with lower toxicity. Therefore, a substantial research is needed for their discovery and improvement. Chemistry of present era aims to build a pollution free environment. For the same, it targets to create some alternativeswhich are eco-friendly and nature loving. Present research work is a step towards achieving such alternatives.

Method:

For this the metallic soaps of copper (derived from common edible oils) were synthesized. The synthesized copper soaps have been confirmed by elemental analysis, UV, and IR spectroscopic technique. The fungicidal activities of copper soaps derived from soyabean, sesame oils have been evaluated by testing against Alternaria alternate and Aspergillus niger by P.D.A. technique.

Result:

The fungi toxicity results indicate that the strain of fungal species are susceptible towards these soaps and suggests that with the increase in concentration of copper soap it may increase further. The transition metallic soaps showed good antifungal activity because chelation increases the anti-microbial potency.

1. INTRODUCTION

Surface active agents are very useful in biological systems, as well as play an important role in many industrial processes [1]. Exact information about micellar feature of copper (II) surfactants play a vital role in its selection in various fields such as foaming, wetting, detergents, emulsifier, herbicides, pesticides, paints, varnishes, wood preservatives, lubricants etc [2]. Anionic soaps containing copper ions play a vital role in various fields such as rubber industries, paints, varnishes, lubrication, protection of crops, stabilization of nylon threads, preservation of wood etc [3]. Inspite of all these applications, copper surfactants derived from various edible oils have not been thoroughly investigated. Many copper complexes are found to have significant anti-tubercular, fungicidal and antitumor activities [4].Several workers described the uses of copper soaps as stabilizers for nylon threads, synthetic polyamides and polyesters [5, 6]. The protection of fabrics, nets, cordage etc from fungi and decay by impregnating them in ammonical solution of copper soaps was described by several workers [7, 8]. The effectiveness of copper soaps as fungicides, bactericides, insecticides and herbicides were also studied. Recent development in metallic soaps preservation shows that zinc and copper napthanates, exhibiting no specific fungal weakness, can be used to prevent attack by wood boring insects the use of copper soaps as driers for the preparation of paints, varnishes and other protective coating. It was observed that the addition of copper soaps to fuel oil reduces the smoke and fumes of burning oil [9]. The use of copper linoleate as heavy-duty wood preservative and many other biological activities of copper metal containing surfactants have also been studied [10]. These facts led us to synthesize copper soaps of sesame and soyabean oils (Fresh and treated at high temperature at different times) and fungicidal activities was planned to study for exploring their applications.

2. EXPERIMENTAL

2.1. Synthesis

Soyabean and sesame oils are easily available in India and chosen for the investigation. Their compositions are recorded in Table 1. Three samples of each oil have been prepared as fresh (untreated), treated oil at high temperature for 15 minutes and for 60 minutes. Copper soaps were prepared by Direct Metathesis process as earlier reported [11] and characterization was done by using elemental analysis, UV, IR methods.

| Name of oil | % Fatty Acids | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16:0 | 18:0 | 18:1 | 18:2 | 18:3 | Other Acids | |

| Sesame Oil | 8 | 4 | 45 | 41 | - | - |

| Soyabean Oil | 12 | 4 | 24 | 51 | 9 | - |

These soaps are abbreviated as follows:

2.2. Determination of Molecular Weight of Copper Soaps

Molecular weights of Cu (II) soaps are determined from S.E [12]. The values of saponification value and molecular weights are recorded in Table 2.

| Name of Copper Soap | Color | M.P. (oC) |

Yield % | Metal % | S.V. | S.E. | Av. Mol. Wt. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Found | Calculated | |||||||

| CSe | Green | 104 | 71 | 10.05 | 9.870 | 191.70 | 292.64 | 646.78 |

| CSo | Green | 108 | 70 | 10.80 | 10.303 | 194.90 | 287.83 | 637.17 |

| CSe15 | Green | 97 | 73 | 13.01 | 13.174 | 252.40 | 222.26 | 506.02 |

| CSo15 | Green | 101 | 72 | 15.98 | 16.116 | 336.60 | 166.66 | 394.82 |

| CSe60 | Green | 80 | 75 | 20.15 | 20.352 | 448.00 | 125.22 | 311.94 |

| CSo60 | Green | 70 | 77 | 10.52 | 10.672 | 210.38 | 266.66 | 594.82 |

|

(1) |

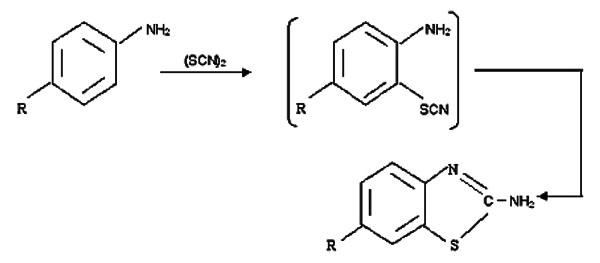

2.3. Reactions During Heating the Oils

2.3.1. Autoxidation

Literature independently suggested that the first reaction was between molecular oxygen and an ethylene bond with formation of peroxide which like hydrogen peroxide, was capable of oxidizing other compounds. It is further suggested that the initially formed peroxide changes by intra-molecular rearrangement to a tautomericenediol- ketohydroxide system. It is believed that the moloxide was the primary product of reaction and this rearranged to the peroxide and confirmed that the primary product of autoxidation of non-conjugated unsaturated acids or esters are hydroperoxides in which the double bond remains intact [13].

2.3.2. Thermal polymerization

When the esters of di and tri ethenoid acids are heated above 200oC, they undergo certain changes. It is confirmed from literature that thermal polymerization of non-conjugated and conjugated octadecadienoates have concluded that the first step in the polymerization of the non-conjugateddienes is isomerization to the conjugated esters and that after configurational change to the trans -trans diene, this enters into diels alder condensation with conjugated or non-conjugateddiene, preferably the latter since this is present in greater proportions [14]. As a result, average molecular weight of oil changes after heating. This fact is supported by several workers that the deterioration during frying is higher in the oils containing higher polyunsaturated fatty acids.

3. CHARACTERIZATION

3.1. Electronic Absorption Spectra

In order to confirm the formation of copper soaps derived from groundnut oil, the electronic absorption spectra was recorded on a Perkin-Elmer-Lambda-28 spectrophotometer.

3.2. Infrared Spectral Analysis

To study the structure of copper soaps derived from oils, the infrared spectra of these compounds in the present study were recorded in KBr disc by making use of Perkin Elmer infrared spectrometer. The IR absorption peaks are given in Table 3.

| Assignments | CSe | CSo | CSe15 | CSo15 | CSe60 | CSo60 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH3 andCH2, C-H Antisym. Stretching | 2975-2953 | 2975-2960 | 2970 | 2627 | 2920 | 2926 |

| CH3 andCH2, C-H Sym. Stretching | 2855-2840 | 2850-2840 | 2860 | 2855 | 2850 | 2854 |

| COO-, C-O Antisym. Stretching | 1590 | 1580 | 1595 | 1590 | 1590 | 1590 |

| CH2 Deformation | 1465 | 1465 | 1460 | 1460 | 1465 | 1461 |

| COO-, C-O Sym. Stretching. | 1375 | 1385 | 1390 | 1418 | 1415 | 1417 |

| CH2 Twisting and Wagging | 1310 | 1310 | 1320 | 1315 | 1320 | 1315 |

| CH3 Rocking | 1170 | 1150 | 1172 | 1169 | 1170 | 1173 |

| CH2 Rocking | 730 | 725 | 725 | 723 | 720 | 723 |

| M-O Stretching | 670 | 669 | 670 | 669 | 665 | 669 |

3.3. Fungicidal Activities

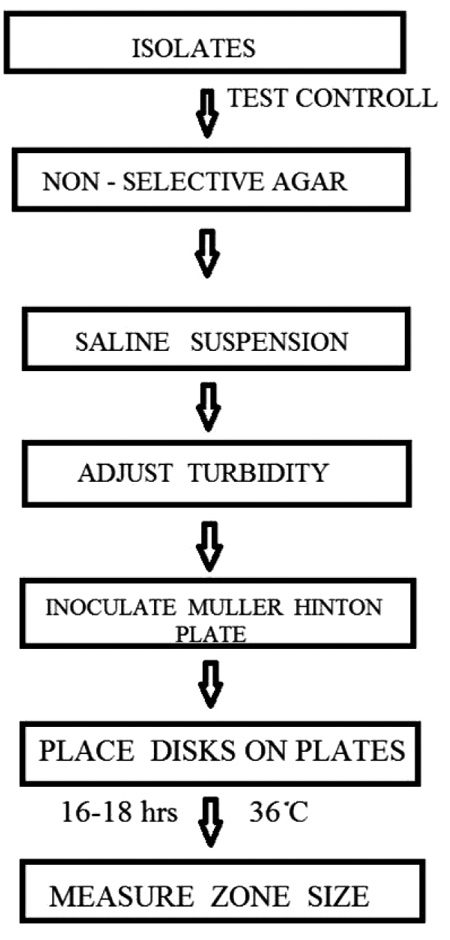

The fungicidal analysis procedure follows below steps as suggested by Booth and Hawks worth as follows:

3.3.1. Sterilization of Glassware’s

For biological activity the glassware were thoroughly washed and cleaned with chromic acid, followed by washed with distilled water and keep them in hot air oven at 160 oC for 24 h. All operations concerning inoculation are done in a completely sterilized chamber.

3.3.2. Inoculation

The artificial induction of micro-organism into a medium is called inoculation. The latter is the most fundamental technique for studying the growth characteristics of micro-organisms and for transfer and maintenance of culture under aseptic condition.

3.3.3. Preparation of Slant

Agar slants were prepared to inoculate microbial culture. To prepare agar slant, a required number of culture tubes were taken and about 12 to 15 ml of liquefied agar medium was poured in each of them. The tubes were now cotton-plugged and sterilized in an autoclave. After the sterilization was over, the tubes were taken out and were placed in slanting (stopping) position for sometimes, the tubes got cooled and the medium in them was solidified resulting in a sloppy surface.

3.3.4. Culture Media Used

In preparing a Culture medium for any micro-organism, the primary goal is to provide a balanced mixture of the nutrient that will permit good growth. Additionally, the culturing of micro-organisms requires Careful Control of various environmental factors which normally are maintained within narrow culture media.

3.3.5. Preparation of PDA

Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) and Potato Dextrose Broth (PDB) are common microbiological media from potato infusion and dextrose (corn sugar) it was prepared by earlier reported method [15].

3.4. Test Organism

The test organism was Alternaria alternate, and Aspergillus niger which was cultured and isolated from its natural habitat and identified morphologically .

3.5. Fungicidal Testing

The fungicidal testing procedure was exactly same as reported by Sharma et al. [16].

The data were statistically analyzed according to the following formula [17].

|

(2) |

(% Inhibition)

C- Total area of fungal colony in plat without copper surfactants after 2 days.

T- Total area of fungal colony in plate with copper surfactants after 2 days.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1. Electronic Absorption Spectra

The spectra give information concerning copper-ligand binding. The electronic absorption spectra of copper sesame soap show that one broad band at about 670-680 nm (14925- 14706 cm-1) and a sharp band at about 280 nm (35714 cm-1). One broad band may be attributed to 2Eg→ 2T2gtransitions arising from MLCTabsorption bands which confirms the formation of copper sesame soap and proposes a distorted octahedral stereochemistry around the metal ion. Absorption peaks (λ<300nm) belong to π→ π* or n→ π* orbital transition of the ligand [18, 19].

4.2. IR Spectra

The detailed infrared absorption spectral studies reveal that there is a marked difference between the spectra of oils and that of corresponding copper soap. In the IR spectra of sesame oil, three distinct bands appear at 3008, 2925 and 2854 cm-1 due to =C-H stretching, -C-H symmetrical and –C-H antisymmetric stretching vibration respectively. Apart from these, oils show characteristic absorption bands of esters (because oils are esters of long chain fatty acids) [20]. In IR spectra of oil, two bands are observed at 1745 and 1164 cm-1. These bands may be assigned to C=O stretching and C-O stretching vibration of ester group. In the spectra of copper soaps, strong band in the region 2970-2840 cm-1 are due to C-H symmetrical and antisymmetrical stretching vibration of methyl and methylene group. There is complete disappearance of the characteristic bands of esters in the spectra of soap molecules and appearance of two new absorption bands in the region 1580-1610 cm-1(symmetricvibration of carboxylate ion) and 1380-1400 cm-1(anti-symmetric vibration of carboxylate ion). The absence of C=O band in the IR spectra of soaps show that there is a resonance in the two C=O bonds of carboxylate group [21, 22]. A number of progressive bands are observed for both oils and soaps in the region 1300-1120 cm-1. Such progressive bands with medium or weak intensity are assigned to the wagging and twisting vibrations of the chain of successive methylene group of the soap molecule. Weak bands in the region 725-710 cm-1 may probably be due to methylene rocking vibrations of the straight carbon chain –(CH2)-. The bands in the region 750-450 cm-1 in the infrared spectra of these soaps are due to metal to oxygen bond stretching vibration. These are called characteristic absorption of metal constituent of each soap molecule [23].In the IR spectra of CSe60 also, bands are present at about 3500 cm-1 (very weak), 1750 cm-1 (strong), 1625 cm-1 (weak) and 1100 cm-1 (weak). Appearance of these bands may be due to formation of various autoxidized products such as ene-diol, keto-hydroxide or carbonyl degradation products. In IR spectra of CSo15 and CSo60 bands are present at 3450 cm-1 and 1745 cm-1 which shows the formation of keto- hydroxide during the autoxidation reactions.

4.3. Fungicidal Activities

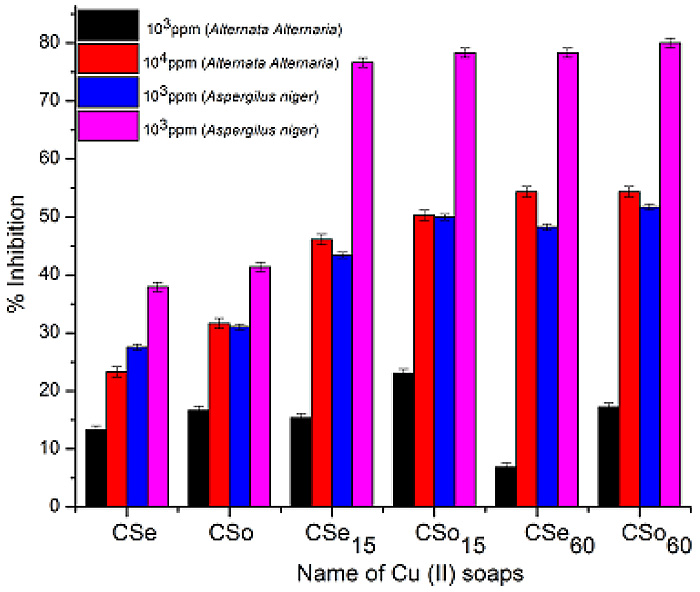

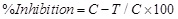

Copper soaps derived from untreated and treated oils have been screened for their anti-fungicidal activity against Alternaria-alternata and Aspergillus-niger at 1000 ppm and 10000 ppm by agar-plate technique [24]. Copper soaps showed moderate activities against both the fungi.

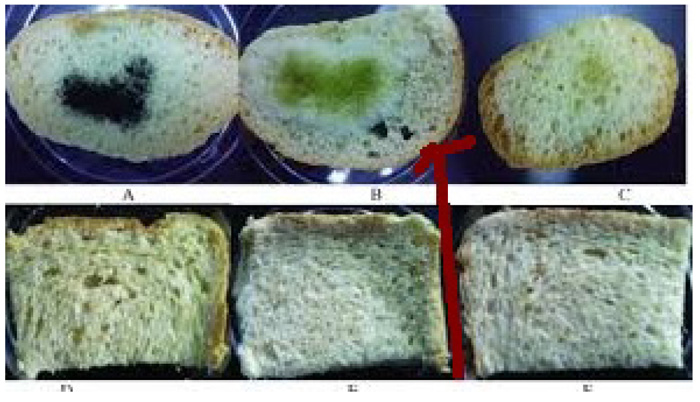

A perusal of Fig. (1) reveals that all the copper soaps have significant fungitoxicity at 10000 ppm but their toxicity decreases markedly on dilution (at 1000 ppm). It is apparent that their efficiency increases with their concentration. Thus it is evident that concentration plays a vital role in increasing the degree of inhibition [25, 26]. Fungicidal screening data revealed that at lower concentration the inhibition of growth is less as compared to higher concentration. From comparison of the results for both the fungi, it is found that all copper soaps are more potent (more toxic) against Aspergillus niger than against Alternaria- alternata i.e. inhibition of growth is higher for Aspergillus niger than inhibition of growth for Alternaria alternate (Figs. 2, 3).

|

Fig. (1). Comparative germ inhibition for Cu (II) soaps derived from treated and untreated oils. |

|

Fig. (2). Presence of Alternaria Alternata on tomato. |

|

Fig. (3). Presence of Aspergillus Niger on bread. |

It reveals that CSe is the least fungi toxic (% inhibition lowest) whereas CSo is the most toxic against both fungi. The activity (toxicity) of copper soaps derived from untreated oils is found to increase in the order:

| CSo > CSe |

For copper soaps derived from treated oils for 15 and 60 minutes, the results are same as copper soaps derived from untreated oils. CSe15, CSe60 is the least active and CSo15CSo60 is the most active against both fungi. The order of activity of copper soaps derived from treated oils for 15 minutes is as follows:

| CSo15 > CSe15 CSo60 > CSe60: |

From comparison of copper soaps derived from untreated and treated sample of oil, it is found that fungitoxicity increases with the increase of time of heating for oils. All the tests were performed in triplicate the standard deviation has been measured by the conventional measure of repeatability and the average was taken as final reading. The results of ANOVA for the antifungal activities for all sops complexes are shown in Table 4 [27, 28].The predicted R2 are in reasonable agreement and closer to 1.0 [29, 30]. This confirms that the experimental data are well satisfactory. The descriptive statics results of Cu (II) soaps shown in Tables 5, 6 confirm satisfactory results in triplet. The result is statistically significant, by the standards of the study, due to p < F.

| CSe60 > CSe15 > CSe |

| CSo60 > CSo15 > CSo |

| Fungi | Cu (II) soap | SS | df | F | P-value | Fcrit | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternaria alternata | CSe | 104 | 1 | 4162 | 0.000240206 | 18.51 | 0.995 |

| CSo | 228 | 1 | 9120 | 0.000109626 | 18.51 | 0.992 | |

| Cse15 | 964 | 1 | 29665 | 3.37084E-05 | 18.51 | 0.996 | |

| CSo15 | 729 | 1 | 16200 | 6.17227E-05 | 18.51 | 0.997 | |

| CSe60 | 2255 | 1 | 82822 | 1.20739E-05 | 18.51 | 0.991 | |

| CSo60 | 1362 | 1 | 54464 | 1.83601E-05 | 18.51 | 0.992 | |

| Aspergilus niger | CSe | 110 | 1 | 4410 | 0.00022668 | 18.51 | 0.992 |

| CSo | 102 | 1 | 4080 | 0.000244984 | 18.51 | 0.996 | |

| Cse15 | 1086 | 1 | 33406 | 2.99332E-05 | 18.51 | 0.997 | |

| CSo15 | 784 | 1 | 17422 | 5.7393E-05 | 18.51 | 0.991 | |

| CSe60 | 900 | 1 | 45000 | 2.22215E-05 | 18.51 | 0.992 | |

| CSo60 | 841 | 1 | 18689 | 5.35034E-05 | 18.51 | 0.995 |

| Alternaria alternata Fungi | Soap |

Concentration (ppm) |

Count | Average % Inhibition | Variance | Coefficient Variance | Std. Deviation | Std. Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSe | 103 | 3 | 13.2 | 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.12 | |

| 104 | 3 | 23.3 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.14 | ||

| CSo | 103 | 3 | 16.5 | 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.11 | |

| 104 | 3 | 31.2 | 0.02 | 0.36 | 0.21 | 0.24 | ||

| CSe15 | 103 | 3 | 15.3 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.32 | |

| 104 | 3 | 46.2 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.22 | ||

| CSo15 | 103 | 3 | 23.4 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.33 | |

| 104 | 3 | 50.4 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.22 | ||

| CSe60 | 103 | 3 | 6.70 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.10 | |

| 104 | 3 | 54.2 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.30 | ||

| CSo60 | 103 | 3 | 17.4 | 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.22 | |

| 104 | 3 | 54.2 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.10 |

| Aspergilus niger Fungi | Soap |

Concentration (ppm) |

Count | Average % Inhibition | Variance | Coefficient Variance | Std. Deviation | Std. Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSe | 103 | 3 | 27.35 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.33 | |

| 104 | 3 | 37.85 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.22 | ||

| CSo | 103 | 3 | 31.35 | 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.10 | |

| 104 | 3 | 41.45 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.30 | ||

| CSe15 | 103 | 3 | 43.40 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.22 | |

| 104 | 3 | 76.35 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.10 | ||

| CSo15 | 103 | 3 | 50.35 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.33 | |

| 104 | 3 | 78.35 | 0.01 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.15 | ||

| CSe60 | 103 | 3 | 48.40 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.22 | |

| 104 | 3 | 78.40 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.22 | ||

| CSo60 | 103 | 3 | 51.35 | 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.22 | |

| 104 | 3 | 80.35 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.22 |

CONCLUSION

From the comparison between IR spectra of Cu (II) soaps of untreated oils and Cu (II) soaps of treated oils, it is found that there is no band in 3200-3600 cm-1 region in Cu (II) soaps derived from untreated oils. But in the IR spectra of copper soaps derived from treated oils, there are bands at about 3400-3500 cm-1, 1750 cm-1, 1625 cm-1, 1100 cm-1. These bands may be due to formation of various autoxidized products such as enediol, keto-hydroxide or carbonyl degradation products. The antifungal activities of copper soaps derived from various edible oils have been evaluated by testing these against Alternaria alternata and Aspergillus niger at different concentrations by agar plate technique. It has been suggested that copper soaps derived from the oils treated for longer period show maximum activity (inhibition of the growth) against both the fungi. Copper soaps derived from oils treated for lesser period show lesser activity and soaps derived from untreated oils show minimum activity against both fungi. The activity (inhibition of the growth) also increases with the increase in concentration of soap. These studies suggested that used oils available in the Indian market can be used as fungicidal, pesticidal or herbicidal agents as they show positive result.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No Animals/Humans were used for studies that are base of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors pay their sincere gratitude to Principal, S.D. Govt. college Beawar and S.P.C. Govt. College Ajmer, Rajasthan (India) for providing necessary research facilities to accomplish this study. IIT, Mumbai is gratefully acknowledged for providing spectral data.